I've never been certain of when this picture was taken and as time passes it becomes less rather than more certain. I can't ask dad anymore and the stories that mum and others tell get more and more contradictory.

In one version it's the day mum and dad met. In another it's the day they went out on their first date. Either way the time difference between the two events (first meeting and first date) can't have been very great.

I remember being told that dad couldn't remember which Tube station they'd agreed to meet at for that first date so he ran from one to the other until he found mum. She was probably late, so the fact that she wasn't at one station wouldn't have ruled it out as being where they were meant to meet. Had dad figured that out about mum already? I think the stations had similar names or variations of the same name but I can't think where that would be now. Maybe it was the exits for different lines of the same name, like Paddington?

If it's true that the picture's from the time of their first meetings then it would be 1956 at the earliest as that's the year they got married on 1 October. That would mean dad was 25. What was I doing then?

Monday 20 September 2010

Wednesday 8 September 2010

How I was born

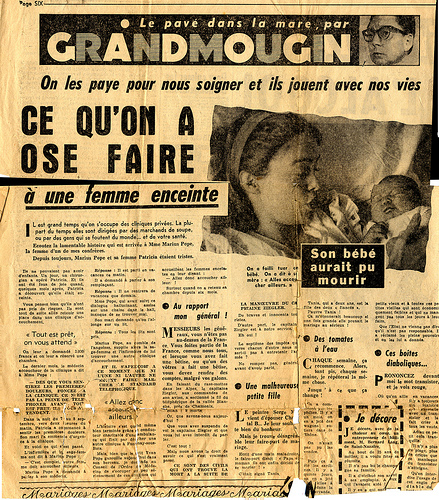

This is the story of how I came to be born. Of course, with my father in his pomp, it had to encompass drama, a foreign country and newspapers. My dad moved to France on a one

year contract to modernise a Parisian rag and during that stay I was

born. They booked a doctor and a clinic, but when the day came it

seems the doctor had gone off on holiday. The replacement was nowhere to

be found. A heatwave was in full swing. Finally a place is found and

the labour goes ahead. My father was a newspaper man, how could such a story not be in the press.

I was a miracle baby. They'd already adopted my sister after

being told no babies could ever be made, but it came to pass that

technology moved on and a fix was found. He told me this story many

times, proud to have created such a memorable event. I was the first

born, and wasn't even supposed to happen.

Dad is not there for the birth, this is Paris, 1961, but he turns up the next morning to visit mother and baby.

"Where is our baby?" he asked.

"I don't know," says my mother, plaintively. He rings the bell and a nurse appears.

"Nurse," he commands. "We would like to see our baby."

A few minutes later another nurse ("she couldn't have been more than fourteen, tiny") appears at the door holding a baby. She holds him up and the parents study it for a while. They smile. "Very nice, thank you," they say. She disappears again with the baby.

Years later I find this photo, the presentation of the lamb.

Thursday 2 September 2010

Portrait of my Father

Portrait of my Father: Jonathan Lethem | Granta 104: Fathers

The picture floats. Someone took it in the Seventies, but the white backdrop gives no clue. My dad owned that wide-lapel trench coat for fifteen or twenty years, typical thrifty child of the Depression. (He probably tried to give it to me at some point.) The beard’s trim narrows the time frame slightly, that rakish full-goatee. So often in later years he wouldn’t have bothered to shave his jaw to shape it. Put this in the early Seventies. Somehow it floated into my collection of paper trinkets, ferried off to college, then to California for a decade. The only copy. By the time I showed it to my father, last week, he hadn’t seen the photograph for thirty-odd years. He couldn’t be sure of the photographer, guessing at three friends with comically overlapping names – Bobby Ramirez, Bob Brooks, Geoff Brooks. (I remember all three of them, beloved rascals from my parents’ hippie posse.) He settled at last on Geoff Brooks. The picture was never framed, nor mounted in an album, just shifted from file cabinet to cardboard box to file cabinet all this time. A scrap of Scotch tape on the left corner reminds me I had it taped up over a desk in Berkeley. In a family that, after my mother’s death, scattered itself and its memorabilia to far corners of the planet, and reassembles now sporadically and sloppily, the picture’s a survivor. But I’ve lived with it for thirty years, gazed into its eyes as often, strange to say, as I have my father’s living eyes.

And it shows Richard Lethem as I dream him, my idol. His Midwestern kindness, prairie-gazer’s soul, but come to the city, donning the beatnik garb, become the painter and poet and political activist he made himself, a man of the city. When I first knew my parents they were, paradoxically, just the two most exciting adults on the scene, part of a pantheon of artists and activists and students staying up late around the dinner table and often crashing afterwards in the extra rooms of the house. My parents were both the two I had the best access to and the coolest to know, the hub of the wheel. I wasn’t interested in childhood, I wanted to hang out with these guys. The picture shows my dad meeting the eyes of a member of his gang, both of them feeling their oats, knowing they were the leading edge of the world. I wanted him to look at me that way. He often did.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)